LIWI BLOG

Rezensionen über neue Bücher & Literaturklassiker, News zu Autoren & Lesungen, Artikelserie „Was macht ein Verlag?“

Nobelpreis für Literatur – Gewinner

Der Nobelpreis für Literatur (schwedisch: Nobelpriset i litteratur) wird jährlich von der Schwedischen Akademie an Autor:innen für herausragende Beiträge im Bereich der Literatur verliehen. Er ist einer der fünf Nobelpreise, die durch das Testament von Alfred Nobel aus dem Jahr 1895 gestiftet wurden.

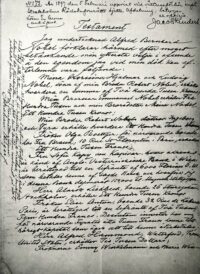

Nobels Testament

Wie in Nobels Testament festgelegt, wird der Preis von der Nobel-Stiftung verwaltet und von der Schwedischen Akademie verliehen. Der erste Literaturnobelpreis wurde 1901 an den Franzosen Sully Prudhomme verliehen. Alle Preisträger:innen erhalten eine Medaille, ein Diplom und ein Preisgeld, das im Laufe der Jahre variiert hat.

1901 erhielt Prudhomme 150.782 SEK, was 2023 etwa 8.823.637,78 SEK entspricht. Der Preis wird jährlich am 10. Dezember, dem Todestag Nobels, in Stockholm verliehen. Und die große Frage für dieses Jahr lautet: Wer bekommt den Literaturnobelpreis 2023? Die nächste Verleihung ist am 10. Dezember 2023.

Der Preis wurde nur einmal posthum verliehen, und zwar an Erik Axel Karlfeldt im Jahr 1931. Und Boris Pasternak musste, als er den Preis erhielt, auf Druck der Regierung der Sowjetunion öffentlich ablehnen.

Jean-Paul Sartre gab 1964 bekannt, dass er den Literaturnobelpreis nicht annehmen wolle, da er in der Vergangenheit stets alle offiziellen Ehrungen abgelehnt hatte. Das Nobelkomitee erkennt jedoch Ablehnungen nicht an und nimmt Pasternak und Sartre in seine Liste der Nobelpreisträger auf.

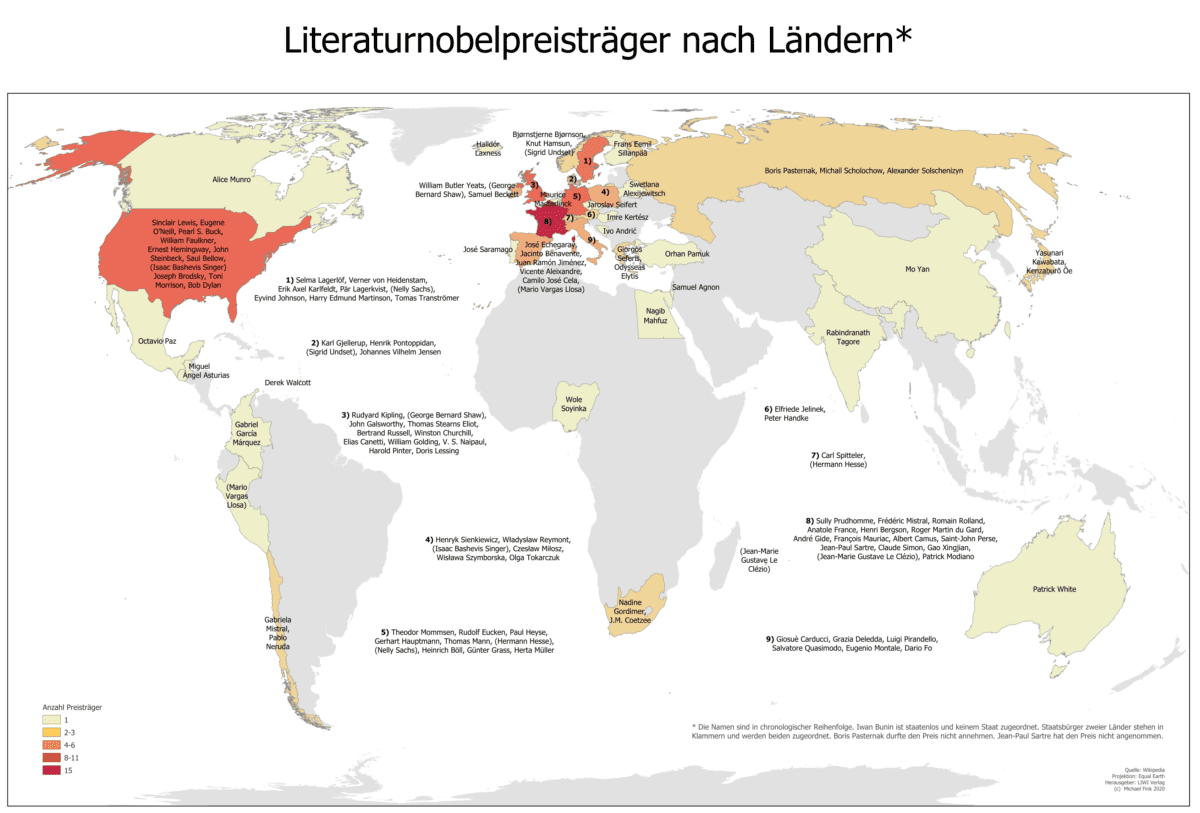

Die Literaturnobelpreis-Weltkarte zeigt eine deutliche Dominanz der Nordhalbkugel. Copyright: Die Karte wurde erstellt von Dr. Michael Fink für den LIWI Verlag. Vielen Dank :-)

Häufig kritisiert wird, dass der Preis meistens an männliche Autoren der Nordhalbkugel vergeben wurde.

Das geographische Ungleichgewicht wird auch auf der obigen Weltkarte deutlich. Und statistisch lässt sich ebenfalls ganz nüchtern feststellen, dass bis 2023 tatsächlich erst siebzehn Frauen den Literaturnobelpreis erhalten haben.

Auffallend ist für manche Kritiker auch, dass einige männliche Autoren, welche heute zu den größten Schriftstellern der Weltliteratur gezählt werden, nie den Literaturnobelpreis erhalten haben.

Hierzu zählen etwa

– Leo Tolstoi mit „Anna Karenina“ und „Krieg und „Frieden“

– Joseph Conrad mit „Das Herz der Finsternis“

– Mark Twain mit „Die Abenteuer Tom Sawyers“ und „Huckleberry Finn“

Selma Lagerlöf, erste weibliche Preisträgerin

Innerhalb der Nordhalbkugel dominieren Preisträger:innen aus Europa und den USA.

Bis 2023 gab es 29 englischsprachige Literaturnobelpreisträger, gefolgt von den Franzosen mit 16 Preisträgern und den Deutschen mit 14 Preisträgern.

Dennoch genießt die alljährliche Preisverleihung ein weltweites Medienecho, und viele längst verstorbene Literaturnobelpreisträger zählen auch heute noch zu vielgelesenen Autor:innen.

Hierzu zählen beispielsweise auch die im LIWI Verlag als Neuausgabe erschienenen Schriftsteller:innen:

– Die erste weibliche Preisträgerin, Selma Lagerlöf.

– Der jüngste Nobelpreisträger aller Zeiten, Rudyard Kipling.

– Der heute noch viel gelesene deutsche Preisträger Gerhart Hauptmann.

Literaturnobelpreis 2024 für Han Kang

Gewinner des Preises 2024 ist die südkoreanische Schriftstellerin Han Kang

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Nun die große Aufzählung: Welche Schriftsteller:innen erhielten einen Nobelpreis für Literatur? Im folgenden findet sich die Liste aller Gewinner:innen des Preises bis 2023 sowie eine Auswahl ihrer wichtigsten Werke.

| Jahr | Preisträger / Geburtsjahr | Land | Begründung der Jury | Bekannte Bücher im Buchhandel* | ||||||

| 2024 | Han Kang (1970) | Südkorea | “for her intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life” | Die Vegetarierin

Menschenwerk Griechischstunden |

||||||

| 2023 | Jon Fosse (1959) | Norwegen | „for his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable“ | Der andere Name | ||||||

| 2022 | Annie Ernaux ( 1940) |

Frankreich | „for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory“ | Die Jahre | ||||||

| 2021 | Abdulrazak Gurnah ( 1948) |

Tansania Großbritannien (Geboren in Zanzibar) |

„for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents“ | Nachleben | ||||||

| 2020 | Louise Glück ( 1943) |

USA | „for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal“ | Averno. Gedichte | ||||||

| 2019 | Peter Handke ( 1942) |

Österreich | „for an influential work that with linguistic ingenuity has explored the periphery and the specificity of human experience“ | Wunschloses Unglück | ||||||

| 2018 | Olga Tokarczuk ( 1962) |

Polen | „for a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life“ | Gesang der Fledermäuse | ||||||

| 2017 | Kazuo Ishiguro ( 1954) |

Großbritannien (geboren in Japan) | „who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world“ | Klara und die Sonne | ||||||

| 2016 | Bob Dylan ( 1941) |

USA | „for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition“ | Lyrics:1962-2012 | ||||||

| 2015 | Svetlana Alexievich ( 1948) |

Belarus Geboren in der Sowjetunion |

„for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time“ | Secondhand-Zeit | ||||||

| 2014 | Patrick Modiano ( 1945) |

Frankreich | „for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the Occupation“ | Im Café der verlorenen Jugend | ||||||

| 2013 | Alice Munro ( 1931) |

Kanada | „master of the contemporary short story“ | Zu viel Glück | ||||||

| 2012 | Mo Yan ( 1955) |

China | „who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary“ | Die Sandelholzstrafe | ||||||

| 2011 | Tomas Tranströmer (1931–2015) |

Schweden | „because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality“ | Sämtliche Gedichte | ||||||

| 2010 | Mario Vargas Llosa ( 1936) |

Peru Spanien |

„for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat“ | Das grüne Haus | ||||||

| 2009 | Herta Müller ( 1953) |

Deutschland / Rumänien | „who, with the concentration of poetry and the frankness of prose, depicts the landscape of the dispossessed“ | Atemschaukel | ||||||

| 2008 | Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio ( 1940) |

Frankreich Mauritius |

„author of new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization“ | Der Goldsucher | ||||||

| 2007 | Doris Lessing (1919–2013) |

Großbritannien Zimbabwe (geboren im Iran) |

„that epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny“ | Das goldene Notizbuch | ||||||

| 2006 | Orhan Pamuk ( 1952) |

Türkeit | „who in the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures“ | Die Nächte der Pest | ||||||

| 2005 | Harold Pinter (1930–2008) |

Großbritannien | „who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression’s closed rooms“ | Theaterstücke | ||||||

| 2004 | Elfriede Jelinek ( 1946) |

Österreich | „for her musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that with extraordinary linguistic zeal reveal the absurdity of society’s clichés and their subjugating power“ | Die Klavierspielerin | ||||||

| 2003 | John Maxwell Coetzee ( 1940) |

Südafrika | „who in innumerable guises portrays the surprising involvement of the outsider“ | Schande | ||||||

| 2002 | Imre Kertész (1929–2016) |

Ungarn | „for writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history“ | Roman eines Schicksallosen | ||||||

| 2001 | Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul (1932–2018) |

Großbritannien Trinidad und Tobago |

„for having united perceptive narrative and incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories“ | An der Biegung des großen Flusses | ||||||

| 2000 | Gao Xingjian ( 1940) |

Frankreich (seit 1998) China (1940–1998) |

„for an oeuvre of universal validity, bitter insights and linguistic ingenuity, which has opened new paths for the Chinese novel and drama“ | Der Berg der Seele | ||||||

| 1999 | Günter Grass (1927–2015) |

Deutschland | „whose frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history“ | Die Blechtrommel | ||||||

| 1998 | José Saramago (1922–2010) |

Portugal | „who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality“ | Die Stadt der Blinden | ||||||

| 1997 | Dario Fo (1926–2016) |

Italien | „who emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden“ | Offene Zweierbeziehung | ||||||

| 1996 | Wisława Szymborska (1923–2012) |

Polen | „for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality“ | Gesammelte Gedichte | ||||||

| 1995 | Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) |

Irland | „for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past“ | Ausgewählte Gedichte | ||||||

| 1994 | Kenzaburō Ōe ( 1935) |

Japan | „who with poetic force creates an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today“ | Der stumme Schrei | ||||||

| 1993 | Toni Morrison (1931–2019) |

USA | „who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality“ | Menschenkind | ||||||

| 1992 | Derek Walcott (1930–2017) |

Saint Lucia | „for a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment“ | Weiße Reiher: Gedichte | ||||||

| 1991 | Nadine Gordimer (1923–2014) |

Südafrika | „who through her magnificent epic writing has – in the words of Alfred Nobel – been of very great benefit to humanity“ | Keine Zeit wie diese | ||||||

| 1990 | Octavio Paz (1914–1998) |

Mexiko | „for impassioned writing with wide horizons, characterized by sensuous intelligence and humanistic integrity“ | Das Labyrinth der Einsamkeit | ||||||

| 1989 | Camilo José Cela (1916–2002) |

Spanien | „for a rich and intensive prose, which with restrained compassion forms a challenging vision of man’s vulnerability“ | Der Bienenkorb | ||||||

| 1988 | Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) |

Ägypten | „who, through works rich in nuance – now clear-sightedly realistic, now evocatively ambiguous – has formed an Arabian narrative art that applies to all mankind“ | Kairoer Trilogie | ||||||

| 1987 | Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996) |

USA Sowietunion |

„for an all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity“ | Ufer der Verlorenen | ||||||

| 1986 | Wole Soyinka ( 1934) |

Nigeria | „who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence“ | Ake. Eine Kindheit | ||||||

| 1985 | Claude Simon (1913–2005) |

Frankreich (Geboren in Madagaskar) |

„who in his novel combines the poet’s and the painter’s creativeness with a deepened awareness of time in the depiction of the human condition“ | Die Akazie | ||||||

| 1984 | Jaroslav Seifert (1901–1986) |

Tscheslowakei (Geboren in Österreich-Ungarn) |

„for his poetry, which endowed with freshness, and rich inventiveness provides a liberating image of the indomitable spirit and versatility of man“ | Alle Schönheiten der Welt | ||||||

| 1983 | William Golding (1911–1993) |

Großbritannien | „for his novels, which with the perspicuity of realistic narrative art and the diversity and universality of myth, illuminate the human condition in the world of today“ | Herr der Fliegen | ||||||

| 1982 | Gabriel García Márquez (1927–2014) |

Kolumbien | „for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts“ | Die Liebe in den Zeiten der Cholera | ||||||

| 1981 | Elias Canetti (1905–1994) |

Großbritannien Bulgarien |

„for writings marked by a broad outlook, a wealth of ideas and artistic power“ | Masse und Macht | ||||||

| 1980 | Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004) |

Polen | „who with uncompromising clear-sightedness voices man’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1979 | Odysseas Elytis (1911–1996) |

Griechenland | „for his poetry, which, against the background of Greek tradition, depicts with sensuous strength and intellectual clear-sightedness modern man’s struggle for freedom and creativeness“ | Ausgewählte Gedichte | ||||||

| 1978 | Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902–1991) |

USA Polen |

„for his impassioned narrative art which, with roots in a Polish-Jewish cultural tradition, brings universal human conditions to life“ | Feinde, die Geschichte einer Liebe | ||||||

| 1977 | Vicente Aleixandre (1898–1984) |

Spanien | „for a creative poetic writing, which illuminates man’s condition in the cosmos and in present-day society, at the same time representing the great renewal of the traditions of Spanish poetry between the wars“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1976 | Saul Bellow (1915–2005) |

USA (Geboren in Kanada) | „for the human understanding and subtle analysis of contemporary culture that are combined in his work“ | Humboldts Vermächtnis | ||||||

| 1975 | Eugenio Montale (1896–1981) |

Italien | „for his distinctive poetry, which, with great artistic sensitivity, has interpreted human values under the sign of an outlook on life with no illusions“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1974 | Eyvind Johnson (1900–1976) |

Schweden | „for a narrative art, farseeing in lands and ages, in the service of freedom“ | Träume von Rosen und Feuer | ||||||

| 1974 | Harry Martinson (1904–1978) |

Schweden | „for writings that catch the dewdrop and reflect the cosmos“ | Die Nesseln blühen | ||||||

| 1973 | Patrick White (1912–1990) |

Australien (Geboren in Großbritannien) |

„for an epic and psychological narrative art, which has introduced a new continent into literature“ | Zur Ruhe kam der Baum des Menschen nie | ||||||

| 1972 | Heinrich Böll (1917–1985) |

Westdeutschland | „for his writing, which through its combination of a broad perspective on his time and a sensitive skill in characterization has contributed to a renewal of German literature“ | Die verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum | ||||||

| 1971 | Pablo Neruda (1904–1973) |

Chile | „for a poetry that with the action of an elemental force brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1970 | Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) |

Sowjetunion | „for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature“ | Der Archipel GULAG | ||||||

| 1969 | Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) |

Irland | „for his writing, which – in new forms for the novel and drama – in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation“ | Warten auf Godot | ||||||

| 1968 | Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972) |

Japan | „for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind“ | Die schlafenden Schönen | ||||||

| 1967 | Miguel Ángel Asturias (1899–1974) |

Guatemala | „for his vivid literary achievement, deep-rooted in the national traits and traditions of Indian peoples of Latin America“ | Der Herr Präsident | ||||||

| 1966 | Shmuel Yosef Agnon (1888–1970) |

Israel (Geboren in Österreich-Ungarn) |

„for his profoundly characteristic narrative art with motifs from the life of the Jewish people“ | Nur wie ein Gast zur Nacht | ||||||

| 1966 | Nelly Sachs (1891–1970) |

Deutschland Schweden |

„for her outstanding lyrical and dramatic writing, which interprets Israel’s destiny with touching strength“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1965 | Mikhail Sholokhov (1905–1984) |

Sowietunion | „for the artistic power and integrity with which, in his epic of the Don, he has given expression to a historic phase in the life of the Russian people“ | Michail Scholochow | ||||||

| 1964 | Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) |

Frankreich | „for his work, which rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth, has exerted a far-reaching influence on our age“ | Der Ekel | ||||||

| 1963 | Giorgos Seferis (1900–1971) |

Griechenland | „for his eminent lyrical writing, inspired by a deep feeling for the Hellenic world of culture“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1962 | John Steinbeck (1902–1968) |

USA | „for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception“ | Früchte des Zorn | ||||||

| 1961 | Ivo Andrić (1892–1975) |

Jugoslawien (geboren in Österreich-Ungarn) | „for the epic force with which he has traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from the history of his country“ | Die Brücke über die Drina | ||||||

| 1960 | Saint-John Perse (1887–1975) |

Frankreich (Geboren in Guadeloupe) |

„for the soaring flight and the evocative imagery of his poetry, which in a visionary fashion reflects the conditions of our time“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1959 | Salvatore Quasimodo (1901–1968) |

Italien | „for his lyrical poetry, which with classical fire expresses the tragic experience of life in our own times“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1958 | Boris Pasternak (1890–1960) |

Sowietunion | „for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition“ | Doktor Shiwago | ||||||

| 1957 | Albert Camus (1913–1960) |

Frankreich (Geboren in Algerien) |

„for his important literary production, which with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times“ | Der Fremde | ||||||

| 1956 | Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881–1958) |

Spanien | „for his lyrical poetry, which in Spanish language constitutes an example of high spirit and artistical purity“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1955 | Halldór Laxness (1902–1998) |

Island | „for his vivid epic power, which has renewed the great narrative art of Iceland“ | Die Islandglocke | ||||||

| 1954 | Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) |

USA | „for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style“ | Der alte Mann und das Meer | ||||||

| 1953 | Winston Churchill (1874–1965) |

Großbritannien | „for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values“ | Der Zweite Weltkrieg | ||||||

| 1952 | François Mauriac (1885–1970) |

Frankreich | „for the deep spiritual insight and the artistic intensity with which he has in his novels penetrated the drama of human life“ | Die Wege des Meeres | ||||||

| 1951 | Pär Lagerkvist (1891–1974) |

Schweden | „for the artistic vigour and true independence of mind with which he endeavours in his poetry to find answers to the eternal questions confronting mankind“ | Barabbas | ||||||

| 1950 | Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) |

Großbritannien | „in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought“ | Philosophie des Abendlandes | ||||||

| 1949 | William Faulkner (1897–1962) |

USA | „for his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel“ | Als ich im Sterben lag | ||||||

| 1948 | Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) |

Großbritannien (Geboren in den USA) |

„for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry“ | Das öde Land | ||||||

| 1947 | André Gide (1869–1951) |

Frankreich | „for his comprehensive and artistically significant writings, in which human problems and conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight“ | Die Falschmünzer | ||||||

| 1946 | Hermann Hesse (1877–1962) |

Deutschland | „for his inspired writings, which while growing in boldness and penetration, exemplify the classical humanitarian ideals and high qualities of style“ | Siddhartha | ||||||

| 1945 | Gabriela Mistral (1889–1957) |

Chile | „for her lyric poetry, which inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1944 | Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (1873–1950) |

Dänemark | „for the rare strength and fertility of his poetic imagination with which is combined an intellectual curiosity of wide scope and a bold, freshly creative style“ | Himmerlandsgeschichten | ||||||

| 1943 | nicht vergeben | |||||||||

| 1942 | nicht vergeben | |||||||||

| 1941 | nicht vergeben | |||||||||

| 1940 | nicht vergeben | |||||||||

| 1939 | Frans Eemil Sillanpää (1888–1964) |

Finnland | „for his deep understanding of his country’s peasantry and the exquisite art with which he has portrayed their way of life and their relationship with Nature“ | Jung entschlafen | ||||||

| 1938 | Pearl Buck (1892–1973) | USA | „for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China and for her biographical masterpieces“ | Die gute Erde | ||||||

| 1937 | Roger Martin du Gard (1881–1958) |

Frankreich | „for the artistic power and truth with which he has depicted human conflict as well as some fundamental aspects of contemporary life in his novel cycle Les Thibault„ | Die Thibaults | ||||||

| 1936 | Eugene O’Neill (1888–1953) |

USA | „for the power, honesty and deep-felt emotions of his dramatic works, which embody an original concept of tragedy“ | Theaterstücke | ||||||

| 1935 | ||||||||||

| 1934 | Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936) |

Italien | „for his bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art“ | Sechs Personen suchen einen Autor | ||||||

| 1933 | Ivan Bunin (1870–1953) |

Staatenlos (Geboren in Rußland) |

„for the strict artistry with which he has carried on the classical Russian traditions in prose writing“ | Verfluchte Tage | ||||||

| 1932 | John Galsworthy (1867–1933) |

Großbritannien | „for his distinguished art of narration, which takes its highest form in The Forsyte Saga„ | Das Herrenhaus | ||||||

| 1931 | Erik Axel Karlfeldt (1864–1931) |

Schweden | „The poetry of Erik Axel Karlfeldt“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1930 | Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951) |

USA | „for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humour, new types of characters“ | Das ist bei uns nicht möglich | ||||||

| 1929 | Thomas Mann (1875–1955) |

Deutschland | „principally for his great novel, Buddenbrooks, which has won steadily increased recognition as one of the classic works of contemporary literature“ | Buddenbrooks | ||||||

| 1928 | Sigrid Undset (1882–1949) |

Norwegen Dänemark |

„principally for her powerful descriptions of Northern life during the Middle Ages“ | Kristin Lavranstochter | ||||||

| 1927 | Henri Bergson (1859–1941) |

Frankreich | „in recognition of his rich and vitalizing ideas and the brilliant skill with which they have been presented“ | Schöpferische Evolution | ||||||

| 1926 | Grazia Deledda (1871–1936) |

Italien | „for her idealistically inspired writings, which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general“ | Schilf im Wind | ||||||

| 1925 | George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) |

Großbritannien Irland |

„for his work which is marked by both idealism and humanity, its stimulating satire often being infused with a singular poetic beauty“ | Pygmalion | ||||||

| 1924 | Władysław Reymont (1867–1925) |

Polen | „for his great national epic, The Peasants„ | Die Bauern | ||||||

| 1923 | William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) |

Irland | „for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1922 | Jacinto Benavente (1866–1954) |

Spanien | „for the happy manner in which he has continued the illustrious traditions of the Spanish drama“ | Theaterstücke | ||||||

| 1921 | Anatole France (1844–1924) |

Frankreich | „in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament“ | Erzählungen | ||||||

| 1920 | Knut Hamsun (1859–1952) |

Norwegen | „for his monumental work, Growth of the Soil„ | Hunger | ||||||

| 1919 | Carl Spitteler (1845–1924) |

Schweiz | „in special appreciation of his epic, Olympian Spring„ | Olympischer Frühling | ||||||

| 1918 | ||||||||||

| 1917 | Karl Adolph Gjellerup (1857–1919) |

Dänemark | „for his varied and rich poetry, which is inspired by lofty ideals“ | Seit ich zuerst sie sah | ||||||

| 1917 | Henrik Pontoppidan (1857–1943) |

Dänemark | „for his authentic descriptions of present-day life in Denmark“ | Hans Im Glück | ||||||

| 1916 | Verner von Heidenstam (1859–1940) |

Schweden | „in recognition of his significance as the leading representative of a new era in our literature“ | Karl der Zwölfte und seine Krieger | ||||||

| 1915 | Romain Rolland (1866–1944) |

Frankreich | „as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production and to the sympathy and love of truth with which he has described different types of human beings“ | Johann Christof | ||||||

| 1914 | nicht vergeben | |||||||||

| 1913 | Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) |

British India ( British Empire) |

„because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West“ | Am Ufer der Stille | ||||||

| 1912 | Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) |

Deutschland | „primarily in recognition of his fruitful, varied and outstanding production in the realm of dramatic art“ | Bahnwärter Thiel | ||||||

| 1911 | Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949) |

Belgien | „in appreciation of his many-sided literary activities, and especially of his dramatic works, which are distinguished by a wealth of imagination and by a poetic fancy, which reveals, sometimes in the guise of a fairy tale, a deep inspiration, while in a mysterious way they appeal to the readers‘ own feelings and stimulate their imaginations“ | Das Leben der Bienen | ||||||

| 1910 | Paul von Heyse (1830–1914) |

Deutschland | „as a tribute to the consummate artistry, permeated with idealism, which he has demonstrated during his long productive career as a lyric poet, dramatist, novelist and writer of world-renowned short stories“ | Novellen | ||||||

| 1909 | Selma Lagerlöf (1858–1940) |

Schweden | „in appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception that characterize her writings“ | Jerusalem | ||||||

| 1908 | Rudolf Christoph Eucken (1846–1926) |

Deutschland | „in recognition of his earnest search for truth, his penetrating power of thought, his wide range of vision, and the warmth and strength in presentation with which in his numerous works he has vindicated and developed an idealistic philosophy of life“ | Die Lebensanschauungen der großen Denker | ||||||

| 1907 | Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) |

Großbritannien | „in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration that characterize the creations of this world-famous author“ | Kim | ||||||

| 1906 | Giosuè Carducci (1835–1907) |

Italien | „not only in consideration of his deep learning and critical research, but above all as a tribute to the creative energy, freshness of style, and lyrical force which characterize his poetic masterpieces“ | Aus den Odi Barbare | ||||||

| 1905 | Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846–1916) |

Polen ( Rußland) |

„because of his outstanding merits as an epic writer“ | Quo Vadis? | ||||||

| 1904 | Frédéric Mistral (1830–1914) |

Frankreich | „in recognition of the fresh originality and true inspiration of his poetic production, which faithfully reflects the natural scenery and native spirit of his people, and, in addition, his significant work as a Provençal philologist“ | Erzählungen | ||||||

| 1904 | José Echegaray (1832–1916) |

Spanien | „in recognition of the numerous and brilliant compositions which, in an individual and original manner, have revived the great traditions of the Spanish drama“ | Dramen | ||||||

| 1903 | Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910) |

Norwegen | „as a tribute to his noble, magnificent and versatile poetry, which has always been distinguished by both the freshness of its inspiration and the rare purity of its spirit“ | Gedichte | ||||||

| 1902 | Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903) |

Deutschland | „the greatest living master of the art of historical writing, with special reference to his monumental work A History of Rome„ | Römische Geschichte | ||||||

| 1901 | Sully Prudhomme (1839–1907) |

Frankreich | „in special recognition of his poetic composition, which gives evidence of lofty idealism, artistic perfection and a rare combination of the qualities of both heart and intellect“ | Poesie | ||||||

Videos

Literaturnobelpreis 2023 für Jon Fosse

Gewinner des Preises 2023 ist der Norweger Jon Fosse, geboren am 29. September 1959 in Haugesund, Provinz Rogaland. Hier spricht er über das Schreiben von Prosa:

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Literaturnobelpreis 2022 für Schriftstellerin Annie Ernaux

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Literaturnobelpreis 2021 für Romanautor Abdulrazak Gurnah

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Der Nobelpreis für Literatur hat im Laufe der Jahrzehnte nicht nur eine enorme kulturelle Strahlkraft entwickelt, sondern auch den Blick auf bisher marginalisierte Literaturen geöffnet. Besonders seit den 1980er-Jahren ist eine verstärkte Internationalisierung zu beobachten: Autorinnen und Autoren aus Afrika, Asien und Lateinamerika rückten stärker ins Rampenlicht. Namen wie Gabriel García Márquez, Wole Soyinka oder Mo Yan markieren diese Erweiterung des literarischen Horizonts und verdeutlichen, dass die Auszeichnung auch ein politisches Signal sein kann – für kulturelle Vielfalt und gegen eurozentrische Begrenzungen.

Zugleich hat sich der Preis immer wieder als Katalysator für die öffentliche Debatte über Literatur und Gesellschaft erwiesen. Auszeichnungen an Autorinnen wie Toni Morrison oder Svetlana Alexijewitsch führten zu Diskussionen über Rassismus, Erinnerungskultur und die Macht der Zeugenschaft. Indem die Akademie Werke würdigt, die sich mit traumatischen historischen Ereignissen oder gegenwärtigen Krisen auseinandersetzen, wird deutlich, dass Literatur nicht im luftleeren Raum existiert, sondern Teil kollektiver Erinnerung und gesellschaftlicher Selbstverständigung ist.

Nicht zuletzt übt die Entscheidung über den Nobelpreis einen erheblichen Einfluss auf den Buchmarkt aus. Preisträgerinnen und Preisträger verzeichnen häufig sprunghaft steigende Auflagen, Übersetzungen in zahlreiche Sprachen und eine intensive mediale Aufmerksamkeit. Dies hat zur Folge, dass auch weniger bekannte Autorinnen und Autoren durch die Auszeichnung ein weltweites Publikum erreichen. Der Nobelpreis fungiert damit nicht nur als literarische Würdigung, sondern auch als ökonomischer und kultureller Motor, der das literarische Feld nachhaltig prägt und verschiebt.

FAQ

Was ist der Nobelpreis für Literatur?

Der Nobelpreis für Literatur ist eine internationale Auszeichnung, die jährlich von der Schwedischen Akademie an Autoren für herausragende Beiträge zur Weltliteratur verliehen wird. Er wurde 1901 ins Leben gerufen und gehört zu den fünf ursprünglichen Nobelpreisen, die von Alfred Nobel in seinem Testament festgelegt wurden.

Nach welchen Kriterien wird der Nobelpreis für Literatur verliehen?

Der Nobelpreis für Literatur wird an einen Autor verliehen, der im literarischen Bereich das Herausragendste in idealistischer Richtung produziert hat. Die Auswahl berücksichtigt das Gesamtwerk eines Autors und nicht ein einzelnes Werk. Die Preisträger werden aufgrund ihrer Innovation, ihres tiefgreifenden Einflusses und ihres Beitrags zur menschlichen Erkenntnis in der Literatur ausgewählt.

Wer wählt die Preisträger aus?

Die Preisträger des Nobelpreises für Literatur werden von der Schwedischen Akademie ausgewählt, die aus 18 Mitgliedern besteht. Diese Mitglieder werden auf Lebenszeit ernannt und sind für die Beurteilung der Nominierten und die Auswahl des Preisträgers verantwortlich.

Wie wird man für den Nobelpreis für Literatur nominiert?

Nominierungen für den Nobelpreis für Literatur können von Mitgliedern der Schwedischen Akademie, Akademien und Professoren der Literatur und Sprachwissenschaft, früheren Nobelpreisträgern für Literatur und Präsidenten von Schriftstellervereinigungen vorgenommen werden. Die Nominierungen sind streng vertraulich, und die vorgeschlagenen Kandidaten werden nicht öffentlich bekannt gegeben.

Wie hoch ist das Preisgeld für den Nobelpreis für Literatur?

Das Preisgeld für den Nobelpreis für Literatur variiert von Jahr zu Jahr. Es wird aus den Zinserträgen des Vermögens finanziert, das Alfred Nobel hinterlassen hat. Im Jahr 2021 betrug das Preisgeld 10 Millionen Schwedische Kronen (ungefähr 1,1 Millionen USD).

Kann der Nobelpreis für Literatur posthum verliehen werden?

Seit 1974 können Nobelpreise, einschließlich des Preises für Literatur, nicht mehr posthum verliehen werden. Wenn ein nominiertes Individuum vor der Bekanntgabe des Preises verstirbt, wird der Preis posthum verliehen, vorausgesetzt, die Person wurde vor ihrem Tod als Preisträger ausgewählt.

Gibt es Kontroversen um den Nobelpreis für Literatur?

Ja, der Nobelpreis für Literatur war im Laufe der Jahre verschiedenen Kontroversen ausgesetzt. Diese reichen von der Auswahl der Preisträger und der Übergehung bedeutender Schriftsteller bis hin zu internen Streitigkeiten innerhalb der Schwedischen Akademie. Kontroversen und Kritik sind Teil der Geschichte des Preises, spiegeln aber auch die Schwierigkeit wider, literarische Exzellenz objektiv zu bewerten.

Wie oft wurde der Nobelpreis für Literatur nicht verliehen?

Der Nobelpreis für Literatur wurde seit seiner Einführung in 1901 mehrmals nicht verliehen, insgesamt sieben Mal. Gründe dafür waren unter anderem Weltkriege sowie Jahre, in denen die Schwedische Akademie keinen Kandidaten als würdig erachtete. 2018 wurde der Preis aufgrund interner Unstimmigkeiten in der Akademie nicht vergeben, aber 2019 wurden zwei Preise verliehen.

Wer sind einige der berühmten Preisträger des Nobelpreises für Literatur?

Zu den berühmten Preisträgern des Nobelpreises für Literatur gehören:

- Bob Dylan (2016), für seine poetischen Neuschöpfungen in der großen amerikanischen Songtradition.

- Alice Munro (2013), Meisterin der zeitgenössischen Kurzgeschichte.

- Gabriel García Márquez (1982), für seine Romane und Kurzgeschichten, in denen das Fantastische und das Realistische miteinander verschmelzen.

- Toni Morrison (1993), deren Romane durch visionäre Kraft und poetische Prägnanz charakterisiert sind.

- Kazuo Ishiguro (2017), der in seinen Romanen von großer emotionaler Kraft die Abgründe unserer illusorischen Welt aufgezeigt hat.

Welche deutschsprachigen Schriftstellerinnen und Schriftsteller haben den Nobelpreis gewonnen?

1902 Theodor Mommsen (DE)

1908 Rudolf Eucken (DE)

1910 Paul Heyse (DE)

1912 Gerhart Hauptmann (DE)

1919 Carl Spitteler (CH)

1929 Thomas Mann (DE)

1946 Hermann Hesse (CH/DE)

1966 Nelly Sachs (DE/SE)

1972 Heinrich Böll (DE)

1981 Elias Canetti (UK/CH)

1999 Günter Grass (DE)

2004 Elfriede Jelinek (AT)

2009 Herta Müller (RO/DE)

2019 Peter Handke (AT)

Kann der Nobelpreis für Literatur an mehr als eine Person verliehen werden?

Ja, der Nobelpreis für Literatur kann geteilt werden, wenn die Schwedische Akademie entscheidet, dass zwei Kandidaten gleichermaßen würdig sind. Dies ist jedoch relativ selten geschehen. Die Entscheidung, den Preis zu teilen, basiert auf der Anerkennung beider Beiträge zur Literatur als herausragend und gleichwertig.

Hat der Nobelpreis für Literatur eine politische Dimension?

Obwohl der Nobelpreis für Literatur primär literarische Errungenschaften würdigen soll, kann die Auswahl der Preisträger auch politische Interpretationen oder Reaktionen hervorrufen. Die Wahl kann als Anerkennung nicht nur künstlerischer, sondern auch politischer oder sozialer Beiträge gesehen werden, die durch das literarische Werk eines Autors geleistet wurden. Die Entscheidungen der Schwedischen Akademie haben manchmal zu Diskussionen über den Einfluss politischer und sozialer Faktoren auf die Preisvergabe geführt.

Wie hat sich der Nobelpreis für Literatur über die Jahre verändert?

Seit seiner ersten Verleihung im Jahr 1901 hat sich der Nobelpreis für Literatur entwickelt, sowohl in Bezug auf die Vielfalt der ausgezeichneten Genres als auch hinsichtlich der geografischen und kulturellen Herkunft der Preisträger. Insbesondere in den letzten Jahrzehnten wurde eine größere Diversität in der Auswahl der Preisträger erkennbar, was die globale Literaturszene besser widerspiegelt.

Welche Kritik gibt es an der Auswahl der Jury?

Kritik an der Auswahl der Jury für den Nobelpreis für Literatur bezieht sich oft auf mangelnde Transparenz und Vielfalt sowie auf die Neigung, bestimmte literarische Traditionen oder Regionen zu bevorzugen. Es gibt auch Vorwürfe, dass bedeutende Autoren übersehen wurden. Die Schwedische Akademie hat Schritte unternommen, um ihre Auswahlverfahren zu überarbeiten und responsiver gegenüber globalen literarischen Bewegungen zu sein.

Gibt es Alternativen zum Nobelpreis für Literatur?

Ja, es gibt mehrere andere internationale Literaturpreise, die als Alternativen oder Ergänzungen zum Nobelpreis für Literatur angesehen werden können. Dazu gehören der Booker Prize, der International Dublin Literary Award und der Prix Goncourt. Diese Preise haben jeweils eigene Kriterien und Schwerpunkte und tragen zur Würdigung literarischer Exzellenz bei.

Wie beeinflusst der Nobelpreis für Literatur die Karriere eines Autors?

Die Verleihung des Nobelpreises für Literatur an einen Autor hat oft einen signifikanten Einfluss auf dessen Karriere. Sie führt in der Regel zu einer erhöhten internationalen Aufmerksamkeit, zu höheren Verkaufszahlen und zu einer Neubewertung des Gesamtwerks des Autors. Für viele Preisträger bedeutet der Nobelpreis eine Bestätigung ihres Lebenswerks und verstärkt ihre Sichtbarkeit auf der globalen literarischen Bühne.

Weitere Literaturpreis – Listen

Verfasst von Thomas Löding, LIWI Blog, zuletzt aktualisiert am 29.09.2025

„Die besten Bücher aller Zeiten“ – Listen zum Stöbern:

- Die besten Bücher aller Zeiten

- 100 Bücher – Die neue ZEIT-Bibliothek der Weltliteratur

- Lieblingsbücher der Briten: BBC Big Read

- Die 100 Bücher des Jahrhunderts von Le Monde

- Der Kanon: Die deutsche Literatur. Reich-Ranickis Liste

- Liste der 100 besten englischsprachigen Romane

- Die besten Bücher von Frauen – Die Kanon – Sybille Berg

- Die besten Bücher 2024

- Liste der 100 besten englischsprachigen Romane

- Die Zeit Bibliothek der 100 Bücher (1980)

- BBC-Auswahl der 100 bedeutendsten britischen Romane

- Schecks Kanon – Die 100 wichtigsten Werke der Weltliteratur

- BBC-Auswahl der 20 besten Romane von 2000 bis 2014

- Elke Heidenreich: Buchtipps & Lieblingsbücher

- Christine Westermann Buchtipps

- Das Literarische Quartett Bücherliste

„Die besten Bücher“ – Auswahl des LIWI Blogs:

- Die besten Bücher von Edgar Allan Poe

- Die besten Bücher von Stefan Zweig

- Die besten Bücher von Fjodor Dostojewski

- Die besten Bücher von Franz Kafka

- Die besten Bücher von Jack London

- Die besten Bücher von Heinrich Heine

- Die besten Bücher von E. T. A. Hoffmann

- Die besten Bücher von Daniel Defoe

- Die besten Bücher von Heinrich Mann

- Die besten Bücher von Joseph Roth

- Die besten Bücher von Rudyard Kipling

- Die besten Bücher von Eduard von Keyserling

- Die besten Bücher von Else Lasker-Schüler

- Die besten Bücher von Arthur Schnitzler

- Die besten Bücher von Gustave Flaubert

- Die besten Bücher von Hans Fallada

- Die besten Bücher von Joseph Conrad

- Die besten Bücher von Novalis

- Die besten historischen Romane

- Die besten Bücher gegen Rechts

- Die besten Bücher für den Sommer

- Die besten Kinderbücher

- Die besten Gedichte von Rainer Maria Rilke

- Die wichtigsten Literaturepochen

- Was ist ein Klassiker?

„Literaturpreis – Gewinner“: